Intro

Medical diagnostic imaging. Findings. Doctors, ordering dozens of imaging studies for their patients daily. Do they have every one of them covered, in case something unexpected is found in a radiology study they ordered?

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, they may not. Due to the busy workflow of a physician, they typically order an imaging study to get more information about the condition they are treating for this particular patient. And, if something incidental that is not directly related to that condition is noted in the radiology report, considering that it requires no immediate action, it may very well go unnoticed during the time of the patient’s stay.

Research show that most of these findings are benign, however some may in future develop into malignancies. Therefore, timely follow-up has to be performed in order to not cause harm to the patient’s health long-term.

This begs the question: how frequently are findings followed up on? In the publications we reviewed, the adherence to follow-up recommendations was found to be underwhelming - only two thirds of these follow-up recommendations tend to be addressed, and unfortunately that is usually a best-case scenario. Most of the time, only half of them tend to be addressed. From a health system perspective, is there anything we can do to ensure that the follow-up recommendations are addressed? We set out to find out. Clear documentation of these findings, streamlined follow-up scheduling workflow, as well as a way to track the process from the time a recommendation is advised up until it is performed would surely help, and there is existing research that prove that.

How do we achieve this? At the end of the day, we want the patients and/or their primary care providers to be aware of every finding in their study. Our multidisciplinary team at Northwestern Medicine attempted to resolve this by creating a system utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) to both help clearly display the findings and follow-ups recommended for every study that is ordered in the health system. The system also helps to make sure that the follow-up is scheduled. More details in the video below.

Overview of the problem and the initial proposed approach

About Us

Northwestern Medicine (NM) is an integrated academic health system based in Chicago. The health system serves more than 1.3 million patients every year across 11 hospitals.

The project team, faced with solving the issue described above, included members from Radiology, Quality, Patient Safety, Process Improvement, Primary Care, Nursing, and Informatics among other teams.

In order to resolve the problem, the team decided to develop an electronic health record (EHR) integrated natural language processing (NLP) system to automatically identify radiographic findings requiring follow-up.

Proposed Result Management Workflow

The Result Management workflow was developed iteratively as we gained more and more insights from the hospital leadership, clinical stakeholders, as well as the data we were working with.

Communication of the identified finding in a given radiology report is carried through the use of the notification system in the EHR, as well as a templated letter informing patients directly that the finding was identified, suggesting them to contact their Primary Care Physician (PCP). A dedicated follow-up team will be closing the communication loop should the identified finding remain unacknowledged by the ordering physician.

The idea of delegating the identification of findings requiring follow-up to an AI model creates a scalable solution that is invisible to the radiologist - their workflow is not affected. In the system that was launched in December 2020 across the NM EHR, all relevant radiology reports continue being screened by the NLP system real-time, triggering notifications to be received by ordering physicians and subsequent workflows, as well as allowing for streamlined ordering of a necessary follow-up. The process also has “safety nets” that are made to make sure that the patient is aware of the finding that is identified as well as the next steps that need to be undertaken.

Project Start: Selected Findings

Two types of findings: lung and adrenal findings were selected based on the inputs from physician stakeholders and their review of the guidelines for management of radiology findings discovered radiographic findings. It is important to keep these two finding types in mind when reading through the rest of the blogpost as they form the basis of and give direction to the overall system design.

The lung findings were selected due to the fact that they are among the most commonly encountered radiographic findings that require additional follow-up. Given the anticipated high volume of lung findings and the well-established follow-up guidelines, lung findings detection has been agreed on to be both a realistic and impactful case for clinical implementation of this system.

In contrast, adrenal findings have a much lower incidence and were selected to test the limits of the system being developed as well as highlight challenges to overcome for future expansion to other findings.

The design phase of the project was initiated in August 2018 and progressed to model development and data acquisition by January 2020. Finally, the Result Management system was deployed in the EHR in December 2020, with continuous monitoring of the use of the system and model performance ongoing to this day.

Initial Modeling (Pre-Annotations)

As for the Data, There is No Data

At the start of the project the team was faced with an issue that is preventing a lot of AI initiatives from becoming reality - the data was unlabeled. In other words, there were millions of radiology reports available for the team to gather insights from, but at the same time, the team had no data-driven way to understand which ones had a follow-up indicated by the radiologist and which did not.

In order to understand how radiologists state the follow-up recommendations in our health system, an Initial corpus of 200 radiology reports was annotated by physicians in the project team.

In order to make the best use of the limited number of samples, the team has decided to use regular expressions (also known as regex) to test if it was a sufficient solution to the problem of identifying findings and the follow-up recommendations in the radiology reports.

Modeling Method I: Regex

This corpus of 200 reports was used to develop a set of regular expressions, with an idea to use them in future to identify the reports with a finding and a suggested follow-up.

Regular expressions are a convenient way to search text for pre-defined phrases.

Note

We will not go into detail describing what regex is, but you can learn more via Python 3’s documentation.

Fourteen regex patterns were developed, each with a goal of capturing a specific finding description provided by the radiologist that was observed in the annotated corpus.

These 14 patterns were able to capture all the findings and recommendations in the initial corpus with 100% sensitivity and specificity as validated by the clinical expert.

When we expanded the dataset with more unlabeled reports to do a more extensive pattern testing, we quickly noticed how the performance downgraded due to new ways of stating the finding and the follow-up. Later, when evaluated on a larger dataset consisting of 10,916 annotated radiology reports, the performance the regex method achieved was at 74% sensitivity and 82% specificity, with an overall accuracy of 77% and positive predictive value of 45%.

In essence, since regex is ultimately a text-search method, it failed to demonstrate good performance on a larger dataset due to the fact that there are endless number of ways a radiologist can state a finding and a recommended follow-up. Misspelled words, extra descriptive sentences in between the finding and the follow-up cause the patterns to not match to the text, resulting in a false negative.

Another point of concern with using regex versus other potential approaches is that guidance on how a follow-up and recommendation must be described in the radiology report changed with time and may change in future, causing the patterns to potentially become totally obsolete.

Finally, the more complicated the text you are searching for with regex, the more complicated the pattern needs to be. And as you can see in the table below, the patterns got quite convoluted already:

Example Text Matched |

Regex Pattern |

|---|---|

Recommend short-term follow-up |

|

Continued imaging is advised |

|

Recommend close 6 month followup |

|

Further evaluation could be considered |

|

Consider further evaluation |

|

Correlation with CT chest suggested |

|

Recommend attention on MRI |

|

Ultrasound may be of use for further evaluation |

|

Can be targeted during tissue sampling |

|

Concern for tumor |

|

Should follow up with |

|

Could be targeted with image-guided biopsy |

|

Biopsy is to be performed. Further evaluation targeting |

|

Continued imaging surveillance to resolution is recommended |

|

As you can imagine, since patterns are manually defined, improving and maintaining tens of patterns like this will be to say the least, challenging.

All in all, regex failed to be flexible enough to identify the reports we were interested in, as well as proved to be not future-proof enough to be used as a model of choice in this problem.

Nevertheless, while being far from the target performance, due to the simplicity of the method, regex provided the team with baseline performance benchmark and, more importantly, the process of reviewing the false negatives and false positives allowed the team to gather insights about the data, i.e. how radiologists tend to state a follow-up. This insight helped shape and direct the future model development process.

Here is a video to recap this section:

Why regex failed and how did it help us understand the problem

Modeling Method II: Machine Learning

The next step up in terms of complexity of the model required to solve the problem after regex was to use traditional Machine Learning (ML) NLP approaches. The idea behind this was that since during training ML models identify useful features in text to make predictions from, they should be better suited to solve the problem as compared to regular expressions, since it will be easier for them to capture the variability of the findings and follow-up recommendations due to a non-rule-based approach in training.

By using the initial corpus of the 200 reports and the bag of words technique to convert the data to tabular format, several traditional ML methods of ranging complexity were evaluated.

After looking at the results, we instantly saw the trend - the more complex the model, the better performance it offered. Taking into account the complexity and variability of the data as well as the modeling task, this makes perfect sense. More complex models are able to capture and identify harder examples correctly, giving them an edge in terms of performance.

However, it is important to understand that using traditional ML models in NLP has one fatal flaw - due to the way the data is preprocessed in order to be a valid input for the model, the order of words is lost. So, the model has no understanding on how one word relates to another whatsoever - it only knows that the given word shows up this number of times in a given report. Another downside of this is that these models will perform differently on the reports of varying length, since the frequency of a common word by default is going to be lower in a shorter report compared to a longer one.

Therefore, while we still have not been able to achieve target performance, the main outcome of this experiment for us was that raising the model’s complexity yields better results.

Modeling Method III: Deep Learning

After we concluded testing ML approaches, continuing on the trend of raising model complexity to resolve our problem, we turned to testing deep learning approaches used in NLP, starting with long short-term memory (LSTM) recurrent neural networks.

Note

You can learn more about how recurrent neural networks work from MIT’s Introduction to Deep Learning lecture.

Deep Learning offers several main advantages over traditional Machine Learning approaches in NLP.

Advantage #1: Varying Input Length

LSTM layer, when used as an input layer to the model, allows the input to be of variable length - therefore, the model should not be biased by the fact that the report is short or long in a way ML models are - the Deep Learning (DL) model is going to look for specific phrases in the report of any length to make a prediction.

Advantage #2: Order of Words

Since the inputs to the LSTM networks is a sequence of tokens from a network’s vocabulary, we can conserve the order of words in the input, allowing us to not lose data integrity and make predictions while taking token-to-token relationships into account.

Advantage #3: Vocabulary

Vocabulary is the mechanism by which DL models can form an understanding of the meaning of the given token during training by evaluating where this token shows up in relation to other tokens. This allows the model to infer word dependencies and meanings from tokens based on their order in the given text.

Moreover, to use the DL capabilities to a full extent, we utilized pre-trained word embeddings to create high-dimensional vector representations of the words in our data - therefore making the input more informative to the model. In our case, we evaluated GloVE as well as BioWordVec embeddings. After extensive testing, GloVE was selected as the embedding of choice since it yielded improved performance, even though BioWordVec was generated using biomedical texts. We believe that GloVE performed better since its training set is more extensive.

For our recurrent network of choice, after testing several different DL architectures, we settled on Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) as the best performing one - its advantage is coming from the ability to process input data in both the forward and backward directions, enabling it to better learn and understand word dependencies in a given text as compared to a traditional LSTM.

It is important to note that Deep Learning models in general tend to have a steeper data requirement compared to Machine Learning. Therefore, before we can truly examine the results of these modeling methods, we need a lot more data than what we had when evaluating regex or ML models. We are going to discuss how we resolved this in the following section on Data Acquisition.

Data Acquisition

As with many real-life machine learning problems, where the outcome of interest is the minority class out of all the other classes in the data, our problem is no different. According to literature the incidence of lung findings in relevant radiology reports is close to 10%, whereas it is lower than 5% for adrenal findings.

Therefore, in our case, the problem was twofold - not only the target class we are trying to predict (a report with a finding and a suggested follow-up) was a minority class, but we also did not have a dataset large enough to support DL model development. Therefore, we decided to acquire these labels ourselves by using a data annotation platform.

Annotation Platform & Data Selected

It is important to note that at the time we were still limited to our initial corpus of annotated reports, so we have made a decision to use the resources in the health system to acquire more labeled data samples to perform training of more complex models discussed in the previous section, as the raw radiology reports coming from the database had no indication of containing a follow-up recommendation or a finding.

In order to resolve this, the team set up an annotation platform alongside the annotation process to allow for a streamlined collection of a high-quality dataset for future modeling. The annotations were performed in-house instead of utilizing a third party service due to the concerns over safety of the data, as well as since it allows more control over the quality of incoming annotations, due to the fact that identifying findings and respective recommended follow-ups requires some degree of medical knowledge.

Annotation Process

After considering the facts above, the online system was set up on our intranet using the open source INCEpTION annotation platform. The annotators–trained clinical nurses–were carefully selected, tasked with selecting relevant text from the curated radiology reports. In order to create a comprehensive dataset for our modeling task, the annotations were asked to highlight the following three items in every report that had a finding and recommendation present:

Finding stated in the report

Follow-up for the finding

Recommended follow-up procedure (if any)

Prior to starting the annotations, each annotator went through a training process developed by the project team. The training process involved both a session explaining in detail what we were looking for in the reports, as well as a quick test to make sure all the annotation goals are clear for the annotator. The test consisted of using the platform to annotate 10 reports with and without follow-up recommendations we annotated internally.

Overview of the annotation process by one of the annotators

We would like to also note that the nurses performing the annotations were all on light-duty restrictions making them unable to fulfill their clinical responsibilities. Annotations were offered to them as one of the ways to perform work remotely and participation was voluntary.

In order to be included in the dataset, each radiology report had to be annotated by three different annotators to account for inter-rater reliability and therefore ensure high quality of the labels. In the case of three annotators making different selections for the report, the report was reviewed internally by our clinical expert to select the right options. If such a report was hard to understand without going into the patient chart to find out more information about the case, it was discarded and not used in the model training process.

To help track the progress of the annotators, the team also utilized the annotation platform to track the rate of annotations as well as the inter-rater reliability to select the reports with the most consistent annotations across different annotators.

The first batch loaded for annotations consisted of 20,000 radiology reports, randomly sampled from a year of data (June 2019 to June 2020) while keeping the procedure type distribution the same to ensure a dataset as diverse as the data the model will be interacting with once deployed. The reports were coming from the procedures that aligned with our curated list of procedures from clinical experts. The goal of the curated list was to identify procedures that could lead to a lung or adrenal finding.

Imaging Study |

Count |

|---|---|

XR CHEST AP PORTABLE |

5,304 |

XR CHEST PA LAT |

5,165 |

CT ABDOMEN PELVIS W CONTRAST |

2,039 |

CT CHEST W CONTRAST |

747 |

XR ABDOMEN AP |

692 |

CT CHEST WO CONTRAST |

669 |

CTA CHEST PE |

635 |

CT ABDOMEN PELVIS WO CONTRAST |

542 |

CT ABDOMEN PELVIS SPIRAL FOR STONE |

370 |

CT CHEST ABDOMEN PELVIS W CONTRAST |

339 |

As the first batch was being annotated, the team noticed that the reported literature rates of findings occurrence were confirmed through the annotations. However, that also meant that most of the reports annotated in the first batch (~90%) contained no findings. While it is important to have enough of a representation of the “negative” class in the ML datasets, after several thousands of examples the value of each new report not containing finding that was being annotated diminished significantly. At the same time, realizing the scarcity of the reports without findings and follow-up recommendations, we wanted more annotated reports of the “positive” class, i.e. with the findings and follow-up recommendations.

Leveraging the previous work, the team trained an ML model (LightGBM) on the annotated dataset, with a goal of identifying new reports that are not yet annotated, but potentially belong to the positive class. The model was optimized for recall to avoid potential bias in the model towards phrases in the already annotated radiology reports.

Further batches that were annotated consisted of a mix of reports that were randomly sampled, as well as targeted towards the class we were lacking annotations at the time. This allowed us to significantly expedite the annotation process required to get to a dataset that allows us to train a deep learning model with acceptable performance. In other words, this gave us the control over the annotation process, allowing us to direct the annotations towards the class we did not have a sufficient number of reports for.

At the end of the annotation process for the lung/adrenal task, the annotators collectively annotated 36,385 reports, of which 17% contained a relevant finding and a follow-up recommendation.

Overview of the annotation platform

Initial Model Development

Data Preprocessing

Annotated reports underwent the following preprocessing steps:

Text converted to lowercase

Trailing whitespace removed

Tokenization

In terms of the samples that were excluded from the dataset, the few reports containing both lung and adrenal-related annotations were excluded.

Model Selection

Four separate NLP models were developed to achieve the goals of extracting target information from the radiology reports:

Image of the NLP model pipeline

At first, each radiology report goes through the Finding/No Finding BiLSTM model, which acts as a binary classifier, separating reports with and without findings and respective follow-up recommendations. In the case when a report is flagged as containing no findings, no other models are initialized.

In case a finding is detected, the models following the first one in the pipeline perform inference on the report in parallel.

For the detailed finding identification (lung/adrenal), another BiLSTM model is used. This model only runs on the report flagged by the initial model, and its task is to identify if the finding in the report is lung-related or adrenal-related.

For comment extraction, an XGBoost model is used, identifying part of the radiology report where the finding and the follow-up are mentioned by the radiologist. This model accepts each tokenized sentence from the radiology report as an individual input, and the prediction probability of each sentence is acquired. Then, the sentence with the highest probability is selected and passed forward in the pipeline.

In case the lung/adrenal model flags report as having lung-related findings, the third BiLSTM model performs inference on the report, with the task of identifying the suggested follow-up procedure. It acts as a binary classifier, selecting between 2 classes:

Recommendation is a Chest CT

Recommendation is not a Chest CT

For the reports that are identified having an adrenal finding, a recommended follow-up is automatically considered to be a referral to endocrinology, as per our clinical experts’ feedback. No model is ran on these reports.

Model Training Process

Model were trained using a 70%/30% train/validation set split. We also performed internal validation on the test set consisting of 10,916 annotated reports to confirm that we are confident in the models’ performance.

To ensure consistency in model training when testing different architectures, splits were performed with a fixed random seed and the same metrics were collected and compared for each trained model: accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, specificity. The metrics were calculated for each classification task along with 95% confidence intervals. For comparison, we also included the regex performance on the same validation dataset discussed previously.

To establish a “human best practice” performance target, we collected the same set of metrics from the annotations collected from our high-performing clinical annotator. This AUC threshold was set at 0.94, which is high, but as you can see from the table overviewing the model performance, our models outperformed them!

Model Type |

Total Number of Reports |

Number of Reports with Follow-up |

AUC |

Accuracy |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baseline Regex |

||||||

Finding / No Finding |

10,916 |

1,857 |

77% |

74% |

82% |

|

Deep Learning (BiLSTM) |

||||||

Finding / No Finding |

10,916 |

1,857 |

0.91 (0.90-0.92) |

95% (94.8-95.5%) |

97.2% (96.3-98.0%) |

85.4% (83.1-87.8%) |

Lung / Adrenal |

1,857 |

1,734 lung; 123 adrenal |

0.87 (0.84-0.88) |

97% (96.8-97.5%) |

98.7% (98.2-99.2%) 1 |

74.7% (70.2-79.3%) 1 |

Ensemble: Lung Finding |

10,916 |

1,734 |

85% |

84.6% |

90.2% |

|

Ensemble: Adrenal Finding |

10,916 |

123 |

95.8% |

57% |

98.5% |

|

CT Recommended vs Other |

1,734 |

1,734 |

0.78 (0.74-0.82) |

81% (78.7-84.2%) |

71% (62.8-79%) |

86.8% (84.9-88.7%) |

Model Deployment Infrastructure

Due to the challenge of making different systems work together as well as integrating the outputs of the NLP pipeline into our health system’s EHR, a considerable effort from several NM teams was required.

To describe the flow of the data in the pipeline, whenever a radiology report from a curated list of procedures was signed in PowerScribe (software used by the radiologists to dictate the radiology reports at NM), it was preprocessed and de-identified before being sent as an input to the NLP models. After the four NLP outputs discussed above were acquired, they were displayed in a notification to the ordering physician accessible through the EHR. The notification is described in detail in the “Clinical workflow” section.

This infrastructure is hosted using the NM Azure environment, with the inference performed using Azure Machine Learning cloud services.

Clinical Workflow & Epic Integration

From the perspective of a radiologist, the implementation of the system has no effect on the workflow. The only requirement that was set for the radiologists was to mention the findings requiring the follow-up in the Impression and/or Findings sections of the signed radiology reports.

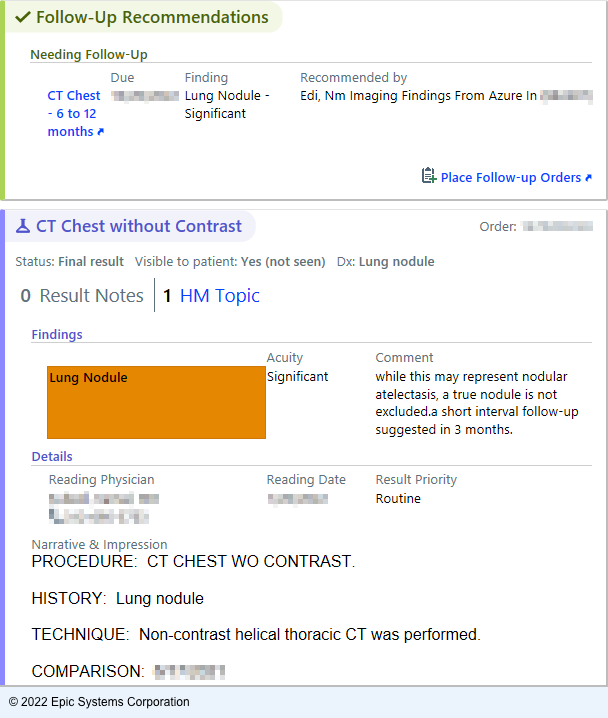

Now, within three minutes of a report resulting, the ordering physician is notified of the NLP Pipeline’s predictions through an InBasket Best Practice Alert. The alert highlights the type of finding identified in the report as well as the relevant report text as determined by the models.

Here is an example of such a notification:

EHR notification image

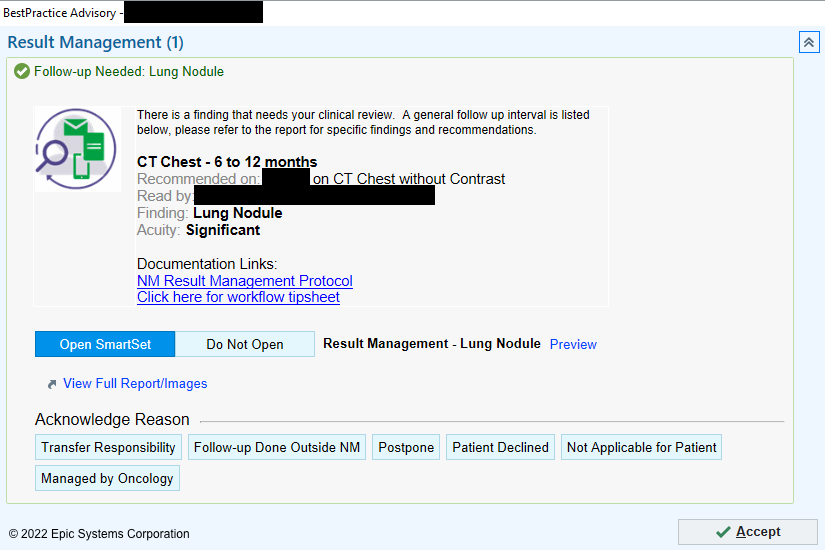

BPA screen once “Place Follow-up Orders” is clicked

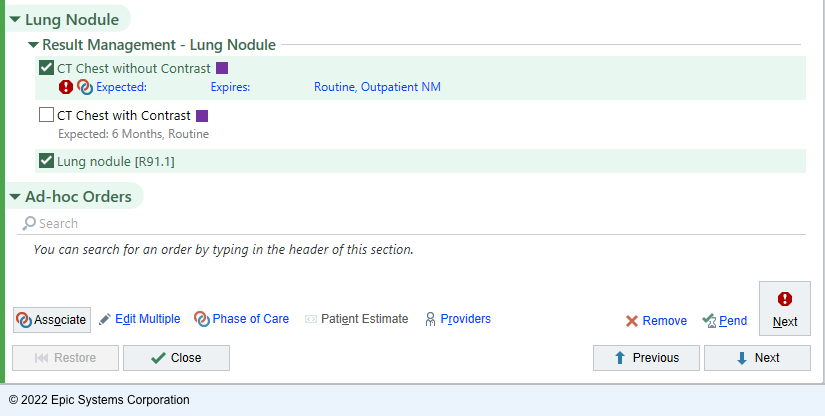

The clickable “Place follow-up orders” link opens the Result Management BPA. Then, either a relevant follow-up can be ordered through a SmartSet tool, or the physician can select an acknowledgment reason to close the workflow loop.

Image with example the responses to the BPA

The SmartSet mentioned previously is automatically populated with a common follow-up orders for a specific finding type. For example, for lung findings, the suggested follow-up is going to be a chest CT with contrast. Once the follow-up is ordered, we can use the built-in Epic functionality to rely on follow-up completion within a specified timeframe. In the case of the patient not completing the ordered follow-up, a dedicated team of nurses is alerted to initiate the communication to make sure the follow-up occurs.

Action |

Count (%) |

|---|---|

Opened SmartSet, no order placed |

887 (17.8) |

Opened SmartSet, lung follow-up placed |

1,378 (27.7) |

Opened SmartSet, adrenal follow-up placed |

9 (0.2) |

Follow-up done outside NM |

65 (1.3) |

Postponed |

975 (19.6) |

Managed by oncology |

904 (18.2) |

Not applicable for patient |

469 (9.4) |

Patient declined |

33 (0.7) |

Transfer responsibility |

258 (5.2) |

Total |

4,978 (100) |

In case of a finding being identified in an Emergency Department encounter, the patient’s Primary Care Physician is notified of the finding and the suggested follow-up. If the patient does not have a Primary Care Physician on record or if the Primary Care Physician is not within the NM health system, the same dedicated team of nurses is alerted, with the task of ensuring that the patient is aware of the necessary follow-up through contacting the patient directly.

In order to ensure that the patient does not miss the follow-up, two additional “safety net” elements were developed.

The first one is notification that the patient receives directly about the follow-up. When seven days pass after the physician receives the BPA notification, the patient will be receiving a MyChart letter, stating that the finding was identified and alerting them to reach out to their physician in case it was not already done. In case a patient does not have MyChart set up, a letter will be mailed using the U.S. Postal Service to the address on file.

The second “safety net” mechanism is an escalation path. It is triggered when no action is taken on the BPA by the receiving physician within 21 days of the notification. In this case, the follow-up team will be notified of the patient’s case to ensure that the finding is addressed appropriately. This mechanism is developed specifically to address the potential InBasket message getting missed within the busy InBaskets.

Overview of the EHR integration process

Prospective Clinical Evaluation

Prospective Evaluation Plan

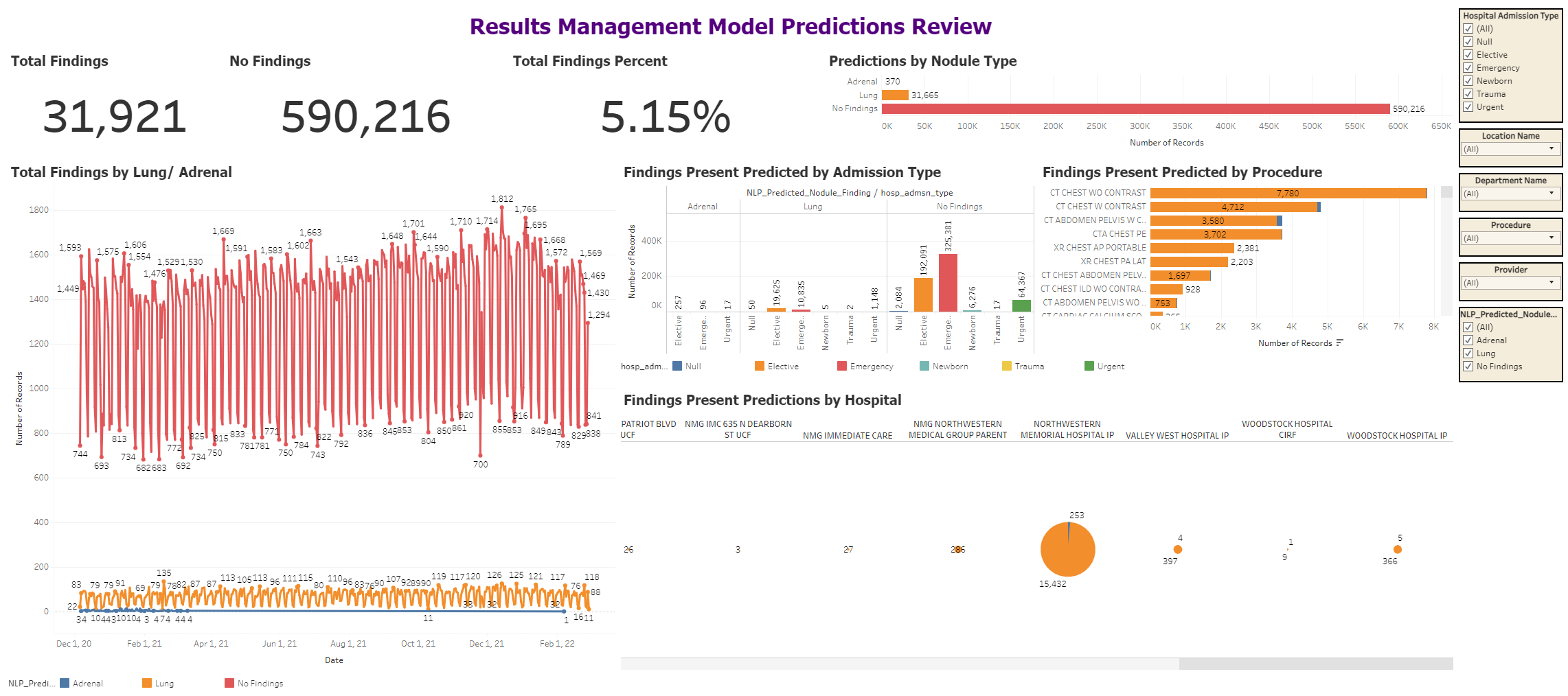

The entire Result Management workflow was rolled out in the health system in December 2020. To ensure that the models are able to maintain the same performance in real-life conditions, we prepared a prospective evaluation plan prior to deployment. The plan was to continuously monitor and evaluate the performance of the deployed system. This is performed through regular reports as well as an online dashboard, aggregating all radiology reports and respective predictions, as well as the associated provider interactions. NLP model performance is manually reviewed, and in a case of a misclassification, they are examined to assess if any changes to the modeling/annotation process need to be applied to change this in the future.

Screenshot of the Prospective Evaluation Dashboard

Imaging Protocol |

Total Number of Reports |

Number of Reports Flagged for Lung Follow-up (%) |

|---|---|---|

CT chest without contrast |

21,861 |

7,217 (33.0) |

CT chest with contrast |

19,938 |

4,427 (22.2) |

CTA chest, pulmonary embolism protocol |

23,851 |

3,420 (14.3) |

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast |

64,256 |

3,370 (5.2) |

XR chest AP portable |

201,880 |

2,231 (1.1) |

XR chest PA LAT |

95,155 |

2,041 (2.1) |

CT chest abdomen pelvis with contrast |

12,556 |

1,520 (12.1) |

CT chest, interstitial lung disease protocol, without contrast |

2,766 |

866 (31.3) |

CT abdomen pelvis without contrast |

15,021 |

698 (4.6) |

CT cardiac calcium score |

2,688 |

328 (12.2) |

The Adrenal Findings Problem

In February 2021, the part of the workflow related to the adrenal findings was suspended, due to concerns over model performance leading to too many false positives. Nevertheless, the predictions of the model were stored and were still running in the back-end on every relevant radiology report. Potential reasons for this were the use of enriched batches for annotations with the goal of having more data samples with adrenal findings, since this biased our performance metrics during training due to having the positive class overrepresented in the training dataset as compared to real-life data.

We wanted to feature this part of our implementation in particular since it highlights both the difficulty of implementing ML solutions in practice and the paramount importance of prospective validation once any system of this sort is deployed, no matter how well the model performed during training.

Overview of the prospective evaluation process

Workflow Challenges

One of the benefits of the system we developed is that it is completely invisible for the radiologists - their day-to-day workflow is not affected by the system. However, it is important to note that at the same time, more responsibility is being placed on the ordering provider, since they are required to interpret the system’s output and determine the suitable next actions for their patient.

From our records, we were able to observe that only 16.9% of the ordering physicians acknowledged the findings highlighted by the system, which is why boosting the clinical uptake remains one of the main focuses of the project to this day. At the same time, we decided not to enforce the physicians to acknowledge the notification to not make the already existing alert fatigue from the intrusive and/or unnecessary EHR notifications worse.

We have also observed the cases when the identified by the system follow-up was ordered for the patient, but as a separate order that was not connected and therefore not tracked through the Results Management system. Consequently, the 16.9% mentioned above may in reality be a lower percentage of physicians who reacted to the implementation.

We suspect that one of the potential causes of this could be the wording on the link that lead to ordering the follow-up. The wording “Place follow-up order” may lead the physicians to believe that no acknowledgement is required in case when a patient does not require a follow-up.

Another potential reason for the low percentage of the acknowledgements to the notification are orders made in the Emergency Department for the patients that do not have an associated Primary Care Physician, as these patients are excluded from the workflow associated with the system and are instead directly managed by the team of follow-up nurses.

We continue to monitor and improve the design of the workflow through the communication and change management via continued feedback from surveys and direct interviews of clinician stakeholders, with the goal of raising the efficacy of the NLP system.

Furthermore, only a quarter of the acknowledgements lead to ordering a follow-up imaging study through the system. This is partially expected as not all follow-up recommendations involve imaging, however, the most common acknowledgement that did not result in a follow-up order are cases when “Managed by Oncology” was selected by the physician. This selection means that these patients already have an established oncological follow-up schedule relating to the finding.

Additionally, a substantial portion of the acknowledgements indicated “Not Applicable for Patient”, or resulted in the physician opening the order SmartSet without any action afterwards. This could mean that either the SmartSet did not include the relevant follow-up procedure, or because the physician decided to order the follow-up in a conventional manner, bypassing the workflow and established monitoring of the system.

Finally, some of these acknowledgements may be a result of the model not making a correct prediction, resulting in a false positive. In order to address this, our prospective evaluation process feedback is incorporated into the development process of the versions of the models.

Another challenge we faced when deploying the system was to not misrepresent the role of the system. We received feedback from several physicians stating that are concerned about the fact that the system is making clinical decisions for their patients instead of them and, on top of it, without their oversight. In reality, this is not the case - the system was put in place to identify the reports with findings and streamline the associated workflow, which was previously nonexistent. In order to combat this, project leaders met with the concerned physicians to clarify the role of AI within the workflow, and as a result the wording of the notification was adjusted to emphasize the fact that it is there to facilitate physician decision-making rather than displace the physician.

Overview of the system by an inpatient physician

Updating the Models

As mentioned previously, the refinement and further development of the AI models continued after the clinical deployment. Main goals of this were to enhance the scalability of the system, as well as improve the overall model performance in response to the feedback we received as well as to the weak points of the AI system identified through prospective validation.

Attention and Transformers

While the type of the neural networks we used initially - LSTM models - process data sequentially, which makes them a great tool when text is the main input the model, they have a substantial downside that needs to be taken into consideration - when the input sequence is too long, due to the way this neural networks work, the model may already “forget” the preceding information by the time it becomes relevant. For example, if there are sentences in between the identified finding and the suggested follow-up, the network may fail to “remember” that the finding was present in the report by the time it is processing the text with the follow-up, and hence this will not trigger the prediction, as the model is identifying the reports with a specific finding that have the relevant follow-up noted. Our solution to mitigate this effect was to use the BiLSTM networks, which perform bidirectional (meaning forward and backward) text processing, decreasing the chance of this happening.

Attention is a mechanism that is developed to preserve relevant context of high importance to the model across the input sequences. Therefore, rather than processing data in chunks like the recurrent models do, attention-based models can draw upon the entirety of the input when processing any given word. Transformer models, in turn, are powerful deep learning architectures that implement self-attention, a form of attention that enables the model to independently learn and attend to the relevant parts of the input data. Since the introduction in 2017, transformer-based models have caused a paradigm shift in NLP, achieving state of the art performance on the language modeling tasks and slowly becoming the go-to model type for real-life NLP solutions.

Another advantage of the transformer-based models is the ability to better parallelize the training process, enabling efficient training on large datasets. As a result, transfer learning strategies have emerged based on initial training of the transformer-based model using an extensive amount of data and compute. These pre-trained models can then be fine-tuned on the smaller focused on the problem dataset in order to specialize the model for the task. This allows to significantly reduce the development time of these types of models since they effectively come ready to be specialized for any NLP task out of the box.

Creating New Models

After evaluating recently developed deep learning NLP model architectures and relevant pretraining strategies, including BERT, BIo+ClinicalBERT, and ELECTRA, we chose to use RoBERTa, an improvement of the BERT transformer architecture for the updated versions of our classification models.

RoBERTa utilizes masked language modeling pre-raining strategy. In this strategy, the fraction of tokens (words or fragments of words) within the input text are masked with a placeholder “[MASK]” token. During the training process, the model is trained to correctly predict these masked tokens with the rest of the text provided as context. As a result, the training process allows the model to create its own version of text understanding during this self-supervised process.

Alongside improving model performance by using a more complex model, utilizing this model instead of the LSTM architecture we were using previously also created an opportunity to enhance scalability and flexibility of our model deployment strategy through creating a universal pre-trained model. This pre-trained RoBERTa model, trained on all of the radiology reports from our institution, would in theory be applicable to all potential future machine learning tasks with a radiology report as the input, whereas our initial plan relied on creating separate models only to perform individual classification tasks. This universal model can then be fine-tuned on individual tasks, such as detection of the follow-up, comment extraction and recommended procedure classification.

Using a more applicable model architecture also allowed us to revise the NLP pipeline and make changes to it without sacrificing performance. While previously the radiology reports went through a Findings/No Findings model first, and then into a Lung/Adrenal finding model, now they would be provided as an input to a single model that would classify them into Lung/Adrenal/No Finding. This prevents the initial Finding/No Finding model from decreasing the overall performance of the pipeline as was the case with the initial NLP Pipeline and was a major factor attributing to the poor performance of the adrenal workflow.

To train this universal RoBERTa model, we obtained a dataset consisting of more than 10 million radiology reports from the health system’s data warehouse (NMEDW) for masked language modeling. Then the universal model was fine-tuned separately on each of the downstream tasks, yielding specialized models all stemming from the “base” one.

We have also changed the text preprocessing strategy as we realized that providing only the Impression section of a radiology report as an input to the model yielded similar results, while resulting in reduced input length, therefore indirectly increasing the input/data quality, as the model has to filter out less information that has no value in terms of the downstream task. This has proven to positively affect the sensitivity and specificity with the newer models.

For the comment extraction model, the downstream task was re-framed from sentence prediction to Extractive Question Answering, in which a model learns to respond to a question through the use of the information provided in the input. Several relevant transformer-based architectures were evaluated for the task, and DistilRoBERTa was selected based on superior performance. Now, this model is provided with the input of the preceding model (Lung/Adrenal finding) as the question to the input radiology report, with the task to identify the relevant portion of the given report which describes the previously identified Lung or Adrenal finding.

Performance of the new RoBERTa models is described in the Table below.

Compared to the BiLSTM models, in terms of lung classification we can observe similar sensitivity with significantly improved specificity, whereas in terms of adrenal classification the sensitivity improved while specificity went down. Additionally, the comment extraction model achieved a Jaccard similarity score of 0.89, indicating very high agreement between model’s selection and what annotators have selected for the given radiology report. This is a significantly better result than the previous sentence classification XGBoost model.

Model Type |

Total Number of Reports |

Number of Reports with Follow-up |

AUC |

Accuracy |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Deep Learning (BiLSTM) 3 |

|||||||

Finding / No Finding |

10,916 |

1,857 |

0.91 (0.90-0.92) |

95% (94.8-95.5%) |

97.2% (96.3-98.0%) |

85.4% (83.1-87.8%) |

|

Lung / Adrenal |

1,857 |

1,734 lung; 123 adrenal |

0.87 (0.84-0.88) |

97% (96.8-97.5%) |

98.7% (98.2-99.2%) 1 |

74.7% (70.2-79.3%) 1 |

|

Ensemble: Lung Finding |

10,916 |

1,734 |

85% |

84.6% |

90.2% |

||

Ensemble: Adrenal Finding |

10,916 |

123 |

95.8% |

57% |

98.5% |

||

CT Recommended vs Other |

1,734 |

1,734 |

0.78 (0.74-0.82) |

81% (78.7-84.2%) |

71% (62.8-79%) |

86.8% (84.9-88.7%) |

|

Deep Learning (RoBERTa) |

|||||||

Lung Finding |

10,916 |

1,734 |

0.90 (0.88-0.92) |

94.7% (99.3.4-96.1%) 2 |

82.2% (78.5-85.9%) |

99.5% (99.1-99.9%) |

|

Adrenal Finding |

10,916 |

123 |

0.81 (0.75-0.89) |

94.7% (99.3.4-96.1%) 2 |

67.4% (61.1-75.6%) |

86.1% (86-86.2%) |

|

CT Recommended vs Other |

1,734 |

1,734 |

0.86 (0.83-0.88) |

87% (85.6-89.4%) |

81.2% (76.7-85.7%) |

90.6% (89.9-91.4%) |

|

The improved models are scheduled to be deployed in March 2022. The prospective evaluation is going to continue, allowing us to continuously monitor and assess model prediction quality.

Overview of the advanced models

Future Plans

Our implementation of the Result Management system signifies the value that can be obtained when using AI to automate any labor-intensive task. The system screens hundreds of radiology reports per day and identifies dozens of follow-up recommendations daily. Our models outperform the previously published methods for finding and follow-up identification, leveraging the advances of deep learning in NLP, as well as robust data collection processes through the annotation framework, supporting model development at scale.

To our knowledge, no previous study has performed prospective clinical evaluation of an AI technique for this problem. The prospective clinical evaluation allowed us to identify and react to the downsides of the perfectly valid initial BiLSTM approach, and rapidly improve on it with existing data.

In the same vein, we believe that continued monitoring of the newer models will allow us to characterize the potential downsides and quickly iterate to produce even better models for the task, translating into clinical benefits.

Moreover, we would like to highlight that the overwhelming majority of such initiatives to use AI to resolve a problem in the clinical space fall short of clinical deployment. Through our work on this, we confirmed that deployment does pose a significant challenge and requires extensive coordination over a long period of time between teams that normally rarely interact. Unexpected changes of model performance, EHR integration, workflow implementation, clinical uptake - these are some of many factors that can be not accounted for initially that can undermine any AI initiative long before deployment.

Next Steps

Due to the fact that clinical uptake of the Result Management workflow has been limited, it is hard to evaluate the global impact on the patient outcomes the system is making. One of the works we reviewed demonstrated significant inter-radiologist variation in rates of follow-up recommendation. There is also a challenge of varying documentation cultures between institutions.

Because of this, we realize that it would be beneficial to assess the generalizability of our models across other health care systems beyond our single-institutional experience. We are also aware of the fact that the models will require re-training in the future as the trends in imaging findings, their documentation, as well as the recommended follow-up studies may change over time, adversely impacting model performance.

We plan to continue building and testing novel NLP techniques as well as adapting our workflow to achieve higher clinical uptake. The prospective evaluation we have been continuously carrying out allowed us to identify radiology reports that may be difficult to classify for the models, and we are constantly adding new annotated reports to our dataset. The EHR infrastructure that we set up together with the NLP pipeline allows us to streamline the processes of model prototyping, evaluation and deployment. Moreover, we are currently working on expanding the system to hepatic, thyroid and ovarian findings requiring follow-up. Finally, as the Result Management system evolves, we will continue to monitor the follow-ups from identification to completion, allowing us to further characterize the true impact on patient outcomes.

Overview of next steps